What Should Your SaaS Marketing Budget Be? Start with Your CAC Allowable

A primer on customer acquisition cost and how to use the metric to guide your growth.

Software companies often look to their lifetime value (LTV) metric for directional guidance on how much they can invest to acquire new customers: the higher the LTV, the more they can spend to acquire a new customer. The LTV/CAC (customer acquisition cost) ratio has become a fan-favorite for assessing the efficacy of paid acquisition programs, with a ratio of 3x+ qualifying as good. But for SaaS companies still in the early innings of their journeys, that ratio is ripe with risk because the LTV inputs—especially the churn metric—are still very raw assumptions.

A powerful way for early stage companies to set and optimize their acquisition program targets is to embrace the concept of a CAC “allowable.”

A quick refresher: defining customer acquisition cost (CAC)

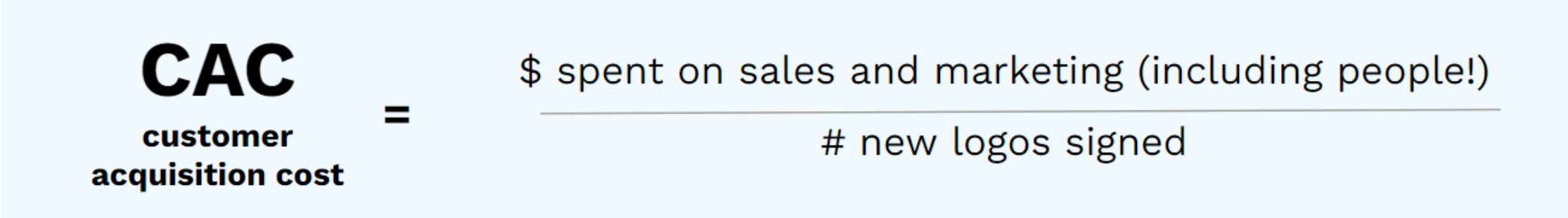

Customer acquisition cost is a simple formula: with all of the dollars spent on sales and marketing, how many new logos (customers) did you successfully sign? Said another way, in a quarter when Company X spent $1 million to acquire 10 new logos, their CAC is $100,000.

Understanding payback periods and CAC allowables

The problem with CAC is that it is completely useless on a standalone basis because it lacks context. In the aforementioned example where Company X has a $100,000 CAC, it’s impossible to say whether or not that’s healthy. It is for this reason that CAC is most often considered in the context of another metric, either LTV/CAC (usually for more mature companies) or payback period. The concept of a payback period is straightforward: how long it takes to recoup the cost required to acquire a new customer on a margin-adjusted basis (don’t forget that last part!).

If Company Y has an average annual contract value of $12,000 and 70% gross margin (meaning they “keep” $8,400 annually) and coincidentally also has a $8,400 CAC, the payback period is exactly one year. If the CAC is $4,200, the payback period is only six months. If the CAC is $16,800, the payback period is two years (yikes).

This begs the question, what is a healthy target payback period? The answer to that question varies wildly; target payback periods will fluctuate based on the go-to-market motions of the business, so it is important to align with your Board on the appropriate target for your company. A 12-month target is often used as a safe answer, but higher-velocity SaaS businesses with smaller contracts may need to be able to recoup costs faster and on the other end of the spectrum, enterprise businesses with large contracts can sometimes stomach payback periods that are much longer than a year.

Translating payback targets into CAC allowables

Once a business has established a target payback period for CAC, they can derive a target allowable. The CAC allowable dictates how much the business can spend to acquire a new customer.

Let’s revisit Company Y from earlier:

- Average customer pays $12,000 per year, or $1,000 per month

- Business has 70% gross margin

- Board gives direction that the business should be able to achieve a 9-month payback

With this information in hand, we can first calculate what a customer would contribute to the business in the 9-month target payback window: $1,000 month × 70% margin × 9 months = $6,300.

Voila! $6,300 is the CAC allowable.

In a world where the Board had pushed the company toward a 6-month payback, the CAC allowable calculation would change to $1,000 month × 70% margin × 6 months, or $4,200.

With a CAC allowable in hand, the growth and revenue teams now know how much they can spend to acquire a new customer.

Budgeting and planning vis-a-vis the CAC allowable

Founders frequently ask me how much they should allocate to a marketing budget, and my answer is always the same: start with a CAC allowable, and if the team is achieving it, let them keep spending! But there is an important nuance to that statement: the team does not need to achieve the CAC allowable in every channel or tactic, just at the aggregate level.

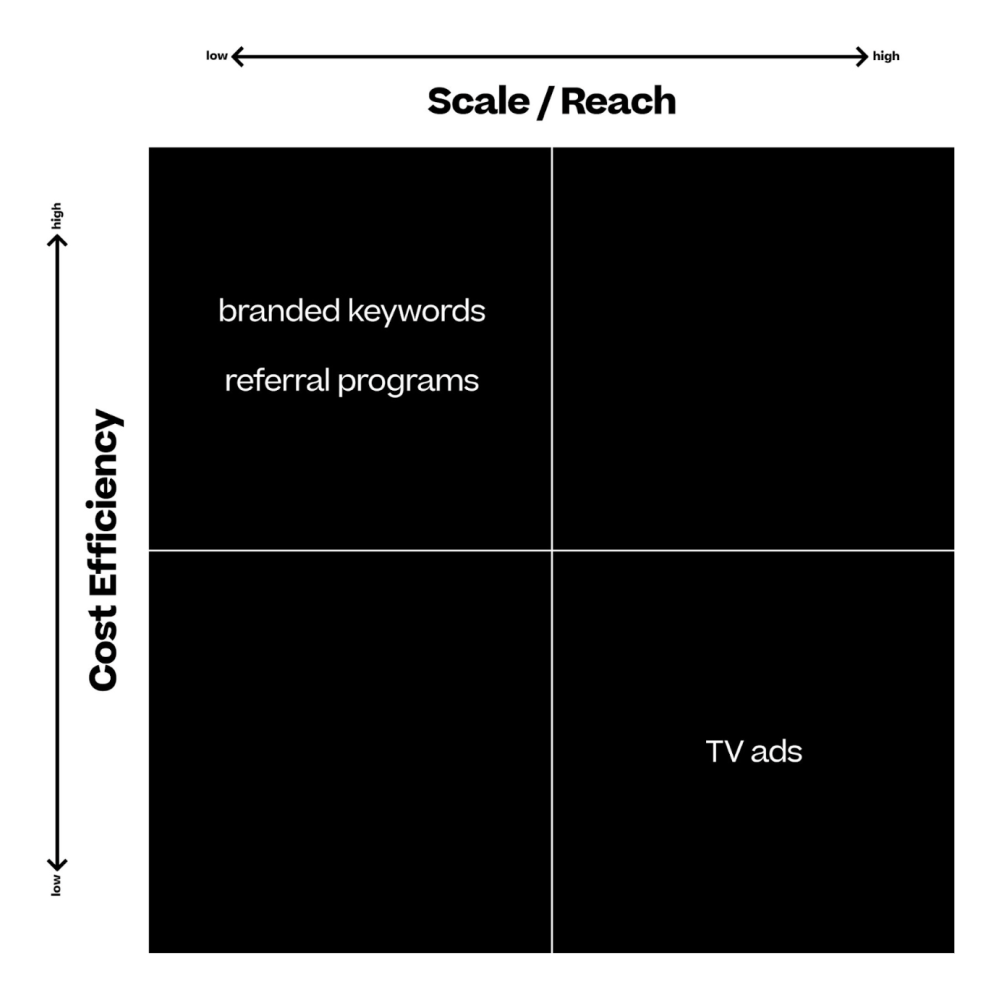

The best growth programs balance both cost efficiency and scale. Branded keywords on Google may be inexpensive, but much to my chagrin, there are only so many people in the world who will search for “Primary Venture Partners” on Google. At the opposite end of the scale, television ads are quite costly (production costs, placement fees, etc.), but the reach is immense. Every scaled company will have some growth programs that aren’t cost-efficient to help them drive scale, but they have enough cost-efficient, higher-intent programs—and a handful of some really, really cost-efficient programs—that the company hits its allowable goals on the aggregate. I frequently refer to this as the “hedge fund” dynamics of growth programs.

Again, if your team is hitting its CAC allowable on the aggregate, let them keep investing!

Walking it up the funnel

Once the CAC allowable is understood, companies can work their way backward up the funnel to set performance targets for cost per lead.

We know from our prior example that the CAC allowable for Company Y is $6,300; using other data from their hypothetical funnel, we can also calculate an allowable for marketing qualified leads (MQLs):

- Company Y Funnel

- Implied MQL > Closed Won conversion = 12.5% (50% × 12.5%)

- CAC allowable = $6,300

- MQL allowable = $787.50 ($6,300 × 12.5%)

The MQL allowable is a powerful derivative metric because top-of-funnel teams have much more control over an MQL allowable week-to-week than they do over a CAC allowable, as customers can take a while to convert. The same “hedge fund” rule applies further up the funnel: if the team can consistently achieve the $787.50 cost per MQL on anaggregatebasis—irrespective of what might be happening with any one campaign—let them keep spending.

Optimizing CAC

To maximize CAC mileage, go-to-market teams must constantly be thinking about how they can influence both parts of the equation: the numerator (the cost component) and the denominator (the volume of new customers signed). There are myriad tried and true tactics for optimizing both, and AI will invariably play a massive role in unlocking further leverage.

CAC optimization: the numerator play

Headcount expense is far and away the most significant driver of the cost equation, so it is imperative to ensure every dollar is being spent as efficiently as possible. Consider these thought starters:

- Can you unlock more leverage from your salary expenses by moving resources to lower-cost geographies (e.g. moving the SDR team from New York to Pittsburgh)?

- Are all of your people focused on their highest-value tasks? Said another way, are senior/more expensive resources completing work that could be done by lower-cost employees? This question applies for every function: AEs managing BDR-level appointment-setting, senior marketers managing programs that could be executed by junior staff, and so forth.

- Are there tools the team could use to increase individual workloads (ultimately reducing the need for incremental headcount)? Yes, AI functionality such as account research and content generation can help, but there are plenty of “old-fashioned” automation tools that will also do the trick: auto-dialers, outbound prospecting and sequencing platforms, etc.

CAC optimization: the denominator play

The most straightforward way to boost the denominator—number of customers signed—is to closely inspect the entire funnel and ensure your team is optimizing both conversion and speed at each step. Best-in-class SaaS organizations are continuously testing new ideas and revisiting the core assumptions of their funnel.

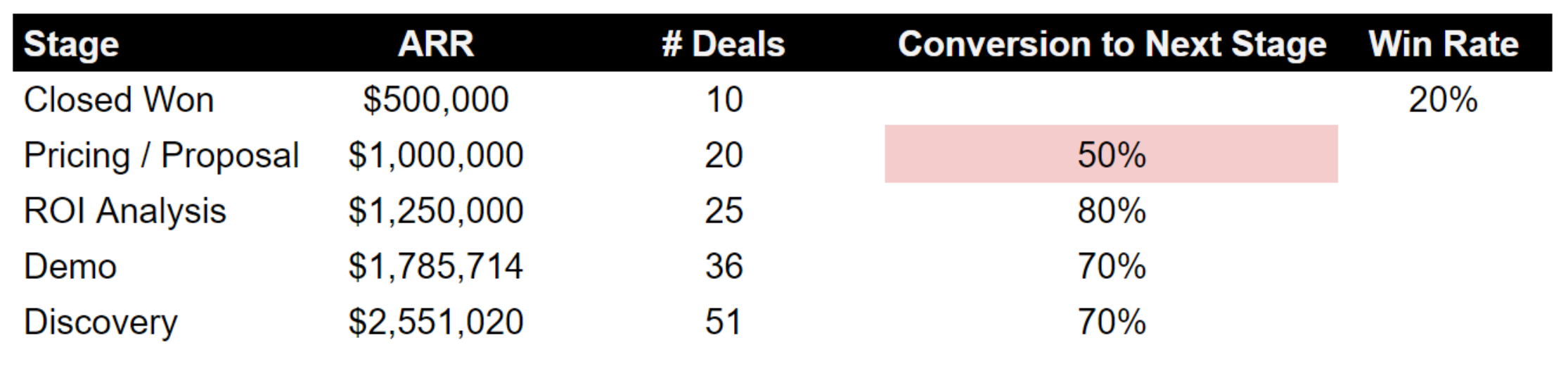

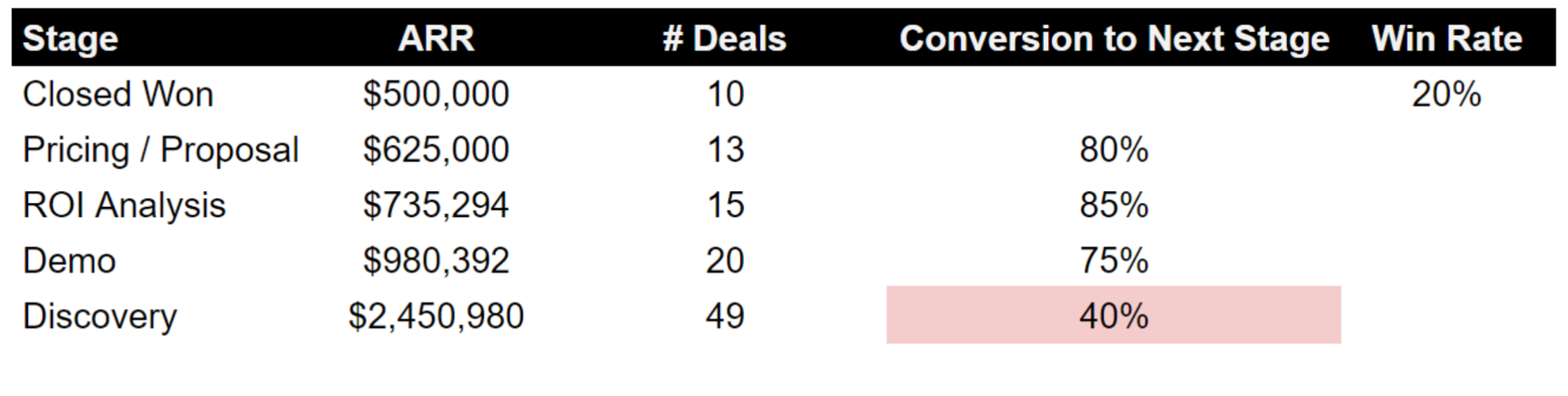

Every SaaS company’s funnel looks different from the next one, so make sure you are focusing on the bottlenecks of your specific business. In the admittedly over-simplified funnel example below, two companies have identical overall win rates of 20%, but very different rate-limiting factors surrounding how they get there: Company X needs to understand why so many deals are falling off at the proposal stage (perhaps the ROI / business case assessment needs work or they weren’t senior enough in the prospect organization in the first place?) whereas Company Y’s greatest optimization opportunity is at the very top of the funnel; low discovery to demo conversion implies they may not be targeting the right customers in the first place.

Company X Funnel Walkback - Focus on Proposal Stage

Company Y Funnel Walkback - Focus on Discovery > Demo Conversion

Editor’s Note: my favorite denominator tactic is to lean on the installed base of current customers for lead referrals, as these deals quickly have higher win rates and faster cycle times than others.

A caveat: CAC allowables are not the be all, end all; cash is king

The CAC allowable is an important construct for companies to understand, but it’s not the be all, end all. Cash is always king, so understanding the “yield” of growth investments is critically important. A SaaS company with an implied CAC payback of 11 months is technically paying back its acquisition costs immediately if they bill annually upfront. Our friend Harry Elliott at General Catalyst wrote a compelling summary of this concept earlier this summer that we highly recommend.

—

CAC and LTV—which was reviewed in detail in last month’sTactic Talk—work together to tell the story of a company’s “unit economics,” which ultimately dictate a company’s ability to profitably scale. When investors ask questions about a SaaS company’s go-to-market “motion,” they usually have unit economics on the brain. If the company claims to rely on product-led growth, is I actually product-led or are there salespeople required (thus challenging the LTV/CAC ratio if contact values are smaller/more PLG-esque)? If a company is investing in a more expensive demand generation approach such as account-based marketing, is LTV strong enough to cover that expense? In the spirit of“First Team” thinking, every SaaS executive must have a command for their company’s unit economics and the role their team can play in optimizing the equation.